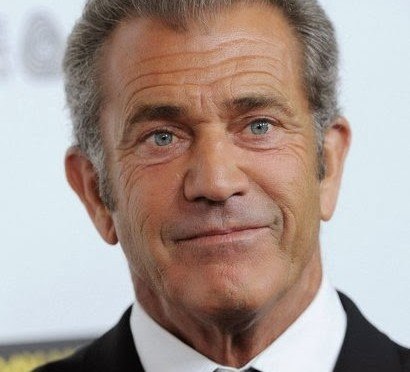

Mel Gibson’s Career — Why He Deserves Another Chance In Hollywood, by Allison Hope Weiner, Deadline|Hollywood, 11 March 2014:

As a journalist who vilified Gibson in The New York Times and Entertainment Weekly until my coverage allowed me to get to know him, I want to make the case here that it is time for those Hollywood agencies and studios to end their quiet blacklisting of Mel Gibson. Once Hollywood’s biggest movie star whose film Braveheart won five Oscars and whose collective box office totals $3.6 billion, Gibson hasn’t been directly employed by a studio since Passion Of The Christ was released in 2004.

For those who are skeptical, I understand. For the longest time, I disliked Gibson and thought he was a Holocaust-denier, homophobic, misogynistic, racist drunk. I wrote as much in articles for EW and the NY Times. And whenever I wrote about him, I would get irate calls from his representatives saying I didn’t know him.

It developed into something that felt like friendship, which doesn’t often happen with investigative journalists and the subjects they cover. Odder still was that it happened with a man disdained by my colleagues, friends and my family, who, like me, are observant Jews. At this point, Gibson’s career had gone all kinds of wrong, starting with that 2006 DUI arrest, when he told that cop that “the Jews are responsible for all the wars in the world.” Four years later, he sounded positively unhinged and racist in surreptitious recordings of an angry phone exchange between Gibson and ex-girlfriend Oksana Grigorieva — the mother of his infant daughter. The whole world heard him shout abusively at her and make racist remarks.

Since then, I’ve gotten to know Gibson extremely well. I thought it would be difficult for him to have a friend in the media, but he has been surprisingly honest and trusting. As a lawyer-turned-reporter, I have no problem asking tough questions, even of friends. Gibson never wavered or equivocated when I confronted him, whether the subject was his drinking, his politics, his religion or his relationships with women. It soon became clear that my early journalistic assessment of him wasn’t right.

This crystallized when we met each other’s families. It was hard to blame his family for being skeptical of a journalist, but the issues with my own family were more challenging. Gibson asked to meet them at my son’s bar mitzvah celebration. Imagine the scene: A room filled with Jews. In walks the person who, in their minds, might be the most notorious anti-Semite in America. Gibson attended alone and I can only imagine what was going through his head when he walked into the party.

Before the evening was over, he was chatting with many of my relatives, who saw a funny, kind, charming guy and not the demon they’d read about. Gutsier still, he attended our Yom Kippur break fast dinner. Anyone who has attended such a gathering knows there is nothing more imposing than making friends in a room full of Jews who haven’t eaten in 24 hours.

I’ve discussed the Holocaust with Gibson and whether his views differed from those of his father. Just as he refused to condemn his father in that TV interview with Diane Sawyer, Gibson refused to discuss his dad with me. Similar to what he told Sawyer, Gibson told me that he believed that 6 million Jews were murdered in the Holocaust. “Do I believe that there were concentration camps where defenseless and innocent Jews died cruelly under the Nazi regime? Of course I do; absolutely,” he told Sawyer. “It was an atrocity of monumental proportion.” In our conversations, I took that a step further. Why, I asked him “did you say those things about the Jews starting all the wars? Where did those unkind things come from?” Gibson thought for a moment, then answered that he’d been terribly hurt by the very personal criticism of him from the Jewish community over The Passion Of The Christ. He said that while he’d been criticized for films before, this was personal and cruel. He said that when he drinks, he can be a mean drunk and “Stuff comes out in a distorted manner…” His own faith led him to make his version of Christ’s story, and he found himself being attacked for making a film that might get Jews killed, and that he was insensitive that his depiction of Jews as Christ’s killer could inflame religious tensions. He was called names by numerous Jewish leaders and a few people literally spat on him. “The criticism was still eating at me,” he told me. “This was a different kind of hammering. A very personal attack.”

Based on my exchanges with Gibson and my own reporting on his transgressions, I’ve stopped doubting him. He worked in Hollywood for 30 years without a single report he was anti-Semitic.

In his second apology on the anti-Semitic statements, Gibson promised to reach out to Jewish leaders. Gibson followed up by meeting with a wide variety of them. He gave me their names when I asked, but Gibson asked me not to publish them because he didn’t want them dragged into public controversy or worse, think he was using them. The meetings were not some photo op to him, he told me, but rather his desire to understand Judaism and personally apologize for the unkind things he said. He has learned much about the Jewish religion, befriending a number of Rabbis and attending his share of Shabbat dinners, Passover Seders and Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur dinners. I believe that effort, along with our conversations, helped him understand why Jewish people reacted as they did to The Passion Of The Christ and why there was Jewish support for the Second Vatican Council. Gibson has quietly donated millions to charitable Jewish causes, in keeping with one of the highest forms of Tzedakah in the Jewish faith, giving when the recipient doesn’t know your identity.

Gibson went well beyond a mea culpa tour. He came out of that experience determined to film the Jewish version of Braveheart. He set at Warner Bros a film about Judah Maccabee, who with his father and four brothers led the Jewish revolt against the Greek-Syrian armies that had conquered Judea in the second century B.C. That seminal story is celebrated by Jews all over the world through Hanukkah, the Festival of Lights.

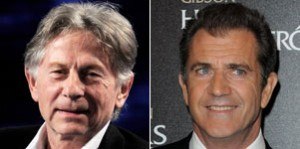

While talent including director Roman Polanski (drugged and sodomized a minor, and fled), Mike Tyson (rape conviction), Chris Brown (beat up ex-girlfriend Rihanna), T.I. (weapons charge), and many others are repped by major agencies, no agency has touched Gibson since Emanuel discharged him as a WME client after those tapes surfaced and he used the “N” word. Gibson has been shunned not for doing anything criminal; his greatest offenses amount to use of harsh language.

Weiner knows that Gibson’s “greatest offense” isn’t “harsh language” aimed at women or blacks, and they aren’t responsible for his “quiet blacklisting”. Weiner identifies herself as a jew and dedicates the bulk of her words to Gibson vis-a-vis jews exactly because she understands that it is jews who have not-so-quietly blacklisted him.

The demonization and blacklisting of Gibson is a reminder that in jew-run Hollywood, talent, popularity and profitability aren’t the primary considerations – jewish sensibilities are. And Gibson will continue to be blacklisted as long as jews collectively regard him as “the most notorious ‘anti-semite’ in America”. Weiner’s explicit appeal to jews, to attempt to convince them otherwise, only calls attention to their power.

Weiner describes Gibson’s grovelling, trying to please and befriend the jews who despise him, as “gutsy”. Yet it is quite the opposite. Even Weiner’s own version of Gibson’s story comes across as serial gutlessness: Lashing out in drunken rage, Gibson bit the hand that fed him, and ever since has been licking the boot that kicks him. Weiner’s suggestion that Gibson’s problem is alcohol, or anger, or both, is also disingenuous. Though he has far more fame and fortune than most of the rest of his race, he has the same main problem. The jewish problem. He could fund and direct some wonderful films about that, but instead gives his love and money to the enemy. Whether such pathological behavior is fueled by Christian beliefs, greed, ambition, or even alcohol – it certainly isn’t guts.

As usual, the jews have tried to make themselves out as the ones who have been harmed. And as usual, this serves to distract from the harm they have done to others. In this case, their handwringing about whether Mel Gibson is or isn’t good for the jews is a distraction from the monstrous harm done by the lies, filth and poison delivered by the judaized media.