Here’s a mainstream media article that makes no bones about the jewish hegemony over US politics. The central point of debate is whether jews think Obama is good or bad for the jews. That they have the power to decide his fortune, one way or the other, is taken for granted.

Here’s a mainstream media article that makes no bones about the jewish hegemony over US politics. The central point of debate is whether jews think Obama is good or bad for the jews. That they have the power to decide his fortune, one way or the other, is taken for granted.

The tone for this exposition of particularist jewish concerns is set right in the title. Tsuris is yiddish slang meaning “trouble or woe; aggravation”. The masters of finance, politics and media are displeased, and they intend for us to know it.

The Tsuris – Why Barack Obama Is the Best Thing Israel Has Going for It Right Now, John Heilemann, New York Magazine, 18 Sept 2011:

Barack Obama is the best thing Israel has going for it right now. Why is that so difficult for Netanyahu and his American Jewish allies to understand?

How, exactly, did Obama come to be portrayed, and perceived by many American Jews, as the most ardently anti-Israel president since Jimmy Carter?

This meme, of course, has been gathering steam for some time, peddled mainly by right-wing Likudophiles here and in the Holy Land. But last week, it took center stage in the special election in New York’s Ninth Congressional District, maybe the most Jewish district in the nation and one held by Democrats since 1923. When the smoke cleared, the Republican had won—and Matt Drudge was up with a headline blaring REVENGE OF THE JEWS.

Obama’s people deny up and down that the loss of a seat last occupied by Anthony Weiner portends, well, pretty much anything for 2012. But the truth is that they are worried, and worried they should be, for the signs of Obama’s slippage among Jewish voters are unmistakable. Last week, a new Gallup poll found that his approval rating in that cohort had fallen to 55 percent—a whopping 28-point drop since his inauguration. And among the high-dollar Jewish donors who were essential to fueling the great Obama money machine last time around, stories of dismay and disaffection are legion. “There’s no question,” says one of the president’s most prolific fund-raisers. “We have a big-time Jewish problem.”

Obama’s team has made its share of errors in the conduct of its diplomacy and in allowing misperceptions to take hold: that its tough-love approach to Israel has been all the former and none of the latter; that its demands on the Palestinians have been either negligible or nonexistent. And many Jewish voters, like those Wall Street financiers (and, to be sure, the overlap between those groups isn’t trivial) who flocked to Obama and were then chagrined when he called them out as “fat cats,” have all too often focused more on the president’s words than his deeds—and come away with the impression that he doesn’t seem to “feel Israel” in his bones.

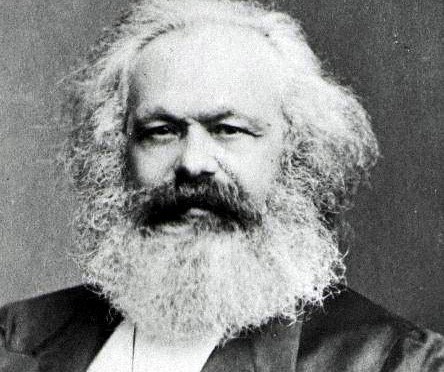

For Obama, such assessments would be funny if they weren’t so frustrating and absurd; and for the Jews who know him best, they are simply mystifying. In the last days of the 2008 campaign, the former federal judge, White House counsel, and Obama mentor Abner Mikva quipped, “When this all is over, people are going to say that Barack Obama is the first Jewish president.” And while that prediction has so far proved to be wildly over-optimistic, there is more truth in it than meets the eye.

The suspicions regarding the bone-deepness of Obama’s bond with Israel were present from the start, and always rooted in a reading of his background that was as superficial as it was misguided. Yes, he was black. Yes, his middle name was Hussein. And yes, in his time in Hyde Park, his friends included Palestinian scholars and activists, notably the historian Rashid Khalidi. But far more crucial to Obama’s makeup and rise to prominence were his ties to Chicago’s Jewish milieu, whose players, from real-estate powerhouse Penny Pritzker to billionaire investor Lester Crown, were among his chief supporters and financial patrons. In 2008—after herculean efforts by his campaign to reassure the Jewish Establishment that he was, er, kosher and stamp out the sub-rosa proliferation of the lie that he is a Muslim—he won 78 percent of the Jewish vote, four points higher than John Kerry’s total four years earlier.

This background meant that, although Obama was hardly an old hand on Israel when he became president, he was well attuned to the Jewish community and its views. “With the kind of exposure he had to Jewish backers, Jewish thinkers, in Illinois,” says deputy national-security adviser Ben Rhodes, “he came into office with a deeper understanding of Jewish culture and Jewish thought than, I would argue, any president in recent memory.”

The American push for a settlement freeze would be the first flash point in Obama’s relations with Israel and also a turning point in his standing with Jewish voters at home. With Netanyahu having just reassumed the prime-ministership in a coalition government that included several ultraconservative parties, he resisted Obama’s call for a freeze. American Jews, meanwhile, saw the administration as aggressively pressuring Israel but treading softly on the Palestinians. In combination with its policy of engagement with Iran, this fostered the impression that Obama’s stance amounted to punishing America’s truest friend in the region while rewarding its—and Israel’s—most lethal foe.

And then there was Netanyahu’s surpassingly volatile governing coalition, which was held together by far-right nationalist, fundamentalist, and even proto-fascistic elements (cf. Avigdor Lieberman).

Omitted: paragraphs detailing yet another Netanyahu snub.

But Netanyahu knew he could get away with it—so staunch and absolute is the bipartisan support he commands in the U.S. Garishly illuminating the point, on the night before his speech to Congress, the prime minister attended the annual AIPAC policy conference in Washington, where he was the headline speaker at the event’s gala banquet. Before he took the stage, three announcers, amid flashing spotlights and in the style of the introductions at an NBA All-Star game, read the names of every prominent person in the room, including 67 senators, 286 House members, and dozens of administration and Israeli officials, foreign dignitaries, and student leaders. (The roll call took half an hour.) When Harry Reid spoke, he obliquely but unambiguously chastised Obama for endorsing the use of the 1967 lines as the basis for a peace deal: “No one should set premature parameters about borders, about building, or about anything else.” The ensuing ovation was deafening—but a mere whisper compared with the thunderous waves of applause that poured over Netanyahu.

The next day came his speech to Congress, in which he spelled out demands that were maximal by any measure: recognition by the Palestinians of Israel as a Jewish state as a precondition for negotiations, a refusal to talk if Hamas is part of the Palestinian side, an undivided Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, and absolutely no right of return for Palestinian refugees.

Exactly one month after his Oval Office awkwardfest with Netanyahu, Obama made the mile-and-a-half trip from the White House to the Mandarin Oriental Hotel to have dinner with several dozen wealthy Jews. His appearance had twin objectives: to rake in more than $1 million and to calm their jangled nerves. Unlike many conservative Jews, the big-ticket Democrats in the room, who had paid $25,000 to $35,800 a head to be there, didn’t believe that Obama was hostile to Israel. Yet it’s fair to say they had their share of qualms and a ton of questions.

In addition to deploying Axelrod and DNC chair Debbie Wasserman Schultz, his campaign has hired an official outreach director to try to fix its Jewish problem: Ira Forman, the former head of the National Jewish Democratic Council. Forman is known for an encyclopedic knowledge of Jewish politics and a history in waging trench warfare against Republican Jewish groups. But none of that will prepare him for the job he is taking on. “A lot of what he’ll be doing is coaxing and persuading,” says a Jewish Obama megabundler. “A lot of people who raised a ton of money for the president last time are very short on enthusiasm for doing it again.”

The hiring of Forman is a tacit acknowledgment that the White House has badly handled the continual care and feeding required to keep major donors sweet—and all the more so in this case. The first White House liaison to the community was Susan Sher, who at the time was chief of staff to Michelle Obama. “Lovely woman, but she knew nothing about Israel,” says an Obama bundler, who some time ago attended a dinner with Sher and a clutch of A-list tribesmen: Mort Zuckerman, HBO co-chief Richard Plepler, Washington Post columnist Richard Cohen. “It was kind of insulting to have this woman talking to these people who know this issue backward and forwards. And then there was no follow-up. Nothing.”

Both the nature and scale of Obama’s Jewish problem—at least where donors are concerned—are tough to pin down. A recent poll by the Republican firm McLaughlin & Associates found that among Jewish donors who gave to Obama in 2008, just 64 percent have already donated or plan to donate to him this time. Complicating the picture is the fact that Jewish buckrakers cite a variety of complaints with Obama: Some object to his rhetoric on Wall Street, some to his economic policies, and some to his handling of Israel.

Omitted: paragraphs explaining why the jewish vote in NY-9 (Anthony Weiner’s vacacted seat) doesn’t matter.

On the other hand, thanks in large part to the indefatigable Ed Koch, who endorsed Obama in 2008 but has now become one of his loudest (and loopiest) critics on Israel, the NY-9 election was framed to an unusual extent as a referendum not just on Obama but on his supposed betrayal of the chosen people. All over TV and the web was Koch, doing a squawky imitation of Romney, saying that the “Obama administration is willing to throw Israel under the bus in order to please the Muslim nations.”

Even in the face of the most pessimistic (for Obama) reading of NY-9, Democrats will comfort themselves with two facts. The first is that, for all the outsize attention they command—and the earsplitting volume of the collective megaphone they wield—Jews make up about 2 percent of the national electorate. Too small a proportion, that is to say, to matter much to the overall popular vote.

The second ostensibly comforting fact for Democrats has to do with the trend lines of recent presidential-election history: Obama’s 78 percent of the Jewish vote, Kerry’s 74 percent, Al Gore’s 79 percent, Clinton’s 78 and 80 percent in 1996 and 1992, respectively. The implication here is that, in the end, the Jews will come home to Obama—mainly because they are overwhelmingly liberal and have nowhere else to go.

The trouble for Republicans is that, in the extant crop of candidates, there is no one who bears even a passing resemblance to Dutch. Though Rick Perry is as avidly pro-Israel as any politician alive—“If you’re our friend, we are with you,” he says. “I’m talking about Israel. Come hell or high water, we will be standing with you!”—his positions on almost every other issue are anathema to virtually every Jew to the left of Eric Cantor. And Perry’s theocratish tendencies have been criticized even by some who are pretty far right; the Christian rally he held in Houston not long before jumping into the race, “The Response,” was derided by Abraham Foxman of the Anti-Defamation League as a “conscious disregard of law and authority” because of the way it traversed the spheres of church and state.

Mitt Romney is an entirely different case. Within the Republican donor class, Romney is the strong favorite. He has actively courted the AIPAC crowd, staking out hawkish positions on Iran and pillorying Obama on Israel. The day before he opened his Florida headquarters earlier this month, Romney dropped in on a local AIPAC meeting in Tampa and was greeted with a standing O. But when it comes to winning over independent Jews or queasy Democratic ones, Romney may have done too effective a job in transforming himself from a pro-choice, pro-gay-rights moderate into a more conventionally conservative candidate. “He’s a phony,” a cheeky Democratic operative notes. “But for a lot of Jews, he may turn out to be just a little too convincing.”

The premise of Obama’s approach to Israel all along has been straightforward. Given the demographic realities it faces—the growth of the Palestinian population in the territories and also of the Arab population in Israel itself—our ally confronts a fundamental and fateful choice: It can remain democratic and lose its Jewish character; it can retain its Jewish character but become an apartheid state; or it can remain both Jewish and democratic, satisfy Palestinian national aspirations, facilitate efforts to contain Iran, alleviate the international opprobrium directed at it, and reap the enormous security and economic benefits of ending the conflict by taking up the task of the creation of a viable Palestinian state—one based, yes, on the 1967 lines with mutually agreed upon land swaps, with East Jerusalem as the Palestinian capital.

The irony is that Obama—along with countless Israelis, members of the Jewish diaspora, and friends of Israel around the world—seems to grasp these realities and this choice more readily than Netanyahu does. “The first Jewish president?” Maybe not. But certainly a president every bit as pro-Israel as the country’s own prime minister—and, if you look from the proper angle, maybe even more so.

Heilemann proceeds from an explicit recognition that jewish financial power (“the non-trivial overlap between jewish voters and Wall Street financiers”) and jewish political contributions (“the high-dollar Jewish donors who were essential to fueling the great Obama money machine”) drive US politics. Clearly this drive extends beyond their current focus on Obama and Israel.

Heilemann idolizes jews and their ethnocentrism. Whether as “the Jewish vote”, “the Jewish Establishment”, “the Jewish community”, “the Jewish diaspora” or just plain old “the Jews”, jews and jewish interests are presented in a purely positive light. This is in stark contrast to the cynical, sinister regard for Whites and White political interests found in most of the mainstream media. Jews are not pathologized for having a group identity, nor are they portrayed negatively for openly arguing about and pursuing their own group interests, independent of the rest of us.

Heilemann and US media pundits and politicians in general treat jewish nationalism with the utmost deference and respect. Though Israel is a jewish ethnostate, ruled by a coalition “held together by far-right nationalist, fundamentalist, and even proto-fascistic elements”, it enjoys the obsequious fealty of Obama and other top US politicians. This may cause consternation for some jews who don’t think it is good for the jews, but their grumbling pales in comparison to the pitiless condemnation and vilification routinely aimed at any form of White nationalism.

Heilemann confides that even the most powerful non-jewish politicians in the US are expected to “feel Israel in their bones”. This is really just one facet of the more general requirement to placate jews, doing whatever they deem best for themselves. But the jews often can’t agree on what they think is best, and so what results is a humiliating, circus-like environment in which US presidents and their challengers regularly profess their love for the jews, only to get kicked in the teeth by one subset of jews or another who don’t find the performance pleasing enough.

Here Heilemann describes Rick Perry as “avidly pro-Israel as any politician alive” and yet “anathema to virtually every Jew to the left of Eric Cantor”. In other words, anathema to virtually every jew. Heilemann’s point is that Obama and every contender for his job each have their own jewish problems, though different in degree. As Heilemann relates the dances these clowns perform to please the jews, what comes through loud and clear is the presumption that the rest of us are immaterial. How this impacts our lives if of no concern. In this way Heilemann indirectly informs us that we all have a jewish problem.

Report: Sarkozy calls Netanyahu ‘liar’ – Israel News, Ynetnews:

Report: Sarkozy calls Netanyahu ‘liar’ – Israel News, Ynetnews: