Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Feedback at the Daily Stormer:

Schlockey – This is mental masturbation. No solutions from this tanjewful.

Such thoughts have occurred to me and to a degree I concur. Philosophy is not my cup of tea. At times it seems to amount to name-checking and pretentious navel gazing. Analysis is reactionary, descriptive rather than proscriptive, more like a post-mortem or obituary than a manifesto. If nothing else however, Yockey provides a springboard for those who are curious to learn more about European history and the thoughts of prominent European thinkers.

In order to propose sensible solutions to a problem you must first identify and understand the problem. As I described when I started this discussion, the claim has been made that Yockey’s Imperium has done just that. I want to believe, but I am skeptical. I would like to understand Yockey’s understanding.

Unlike many other analysts, Yockey relatively clearly identifies the jews. He also quite correctly describes the jews and the nature of the jewish problem as parasitic. Unfortunately, as I begin to come to grips with in this installment, Yockey had an iconoclastic attitude about race. He regarded soul/spirit/culture above and before people/biology/genes/materialism.

I began this second series to focus on Yockey’s view of what he described as “vertical race”, which he associated with the 19th century and looked down upon, and “horizontal race”, which he associated with the 20th century and advocated in favor of. It occurs to me now however that he provides a worthwhile introduction and synopsis of his views in the very first pages of Imperium. At page 10 he describes the thesis of his book – problem and solution:

The great crisis of the West set in forcefully with the French Revolution and its consequent phenomena. Napoleon was the symbol of the transition of Culture into Civilization — Civilization, the life of the material, the external, of power, giant economies, armies, and fleets, of great numbers and colossal technics, over Culture, the inner life of religion, philosophy, arts, domination of the external life of politics and economics by strict form and symbolism, strict restraint of the beast-of-prey in man, feeling of cultural unity. It is the victory of Rationalism, Money and the great city over the traditions of religion and authority, of Intellect over Instinct.

11

We had seen all this in the previous high cultures as they approached their final life-phase. In each case the crisis had been resolved by the resurgence of the old forces of Religion and Authority, their victory over Rationalism and Money, and the final union of the nations into an Imperium.

Yockey’s vision tends toward dichotomies. Behind everything he anthropomorphizes opposing forces, names capitalized, distinct and at odds. With Culture, however, he waves his hands and describes the literally inorganic as organic:

The High Cultures belong at the peak of the organic hierarchy: plant, animal, man. They differ from the other organisms in that they are invisible, or in other words, they have no light-quality. In this they resemble the human soul. The body of a High Culture is made up of the population streams in its landscape. They furnish it with the material through which it actualizes its possibilities.

Since a Culture is organic, it has an individuality, and a soul. Thus it cannot be influenced in its

12

depths from any outside force whatever. It has a destiny, like all organisms. It has a period of gestation, and a birth-time. It has a growth, a maturity, fulfillment, a down-going, a death.

So, what crisis? Organisms live and die. If this is natural, where is the crisis? Skipping ahead to page 62 we get the impression that what disturbed Yockey was the sort of realization that disturbs many of us, even those who are less intelligent and knowledgable:

The proud Civilization which in 1900 was master of 18/2Oths of the earth’s surface, arrived at the point in 1945, after the suicidal Second World War, where it controlled no part whatever of the earth.

In 1900, the State-system of Europe reacted as a unit when the negative will of Asia thought, by the Boxer rebellion, to drive out the Imperialism of the West from China. Western armies from the leading States moved in, and smashed the revolt. Less than half a century later, extra-European armies are moving freely about Europe, armies containing Negroes, Mongols, Turkestani, Kirghizians, Americans, Armenians, colonials and Asiatics of all areas. How did this happen?

Quite obviously, through the inner division of the West. This division was not material — material cannot divide men if their minds agree. No, it was spiritual division that brought Europe into the dust. Half of Europe had a completely different attitude toward Life, a different valuation of Life, from the other half. The two attitudes were respectively the 19th century outlook, and the 20th century outlook.

Yockey here describes the What, not the How. The How, in a word, is jews. Jews were the masters of “the proud Civilization” even before what Yockey describes as a sudden change in control. Control did not actually change – it simply became clear that Whites were not in control.

Yockey refers to his solution as “The Idea”:

The first step in action is thus the liquidation of the spiritual division of Europe. There is only one basis on which this can be done; there is only one Future, the organic Future. The only changes that can be brought about in a Culture are those which its life-stage necessitates. The 20th century outlook is synonymous with the Future of the West, the perpetuation of the 19th century outlook means the continuation of the domination of the West by Culture-distorters and barbarians. The task of the present work is the presentation of all the fundamentals of the

64

20th century outlook necessary as the framework for comprehending and thorough action. First is the Idea — not an ideal which can be summed up in a catchword, or one which can be explained to an alien, but a living, breathing, wordless feeling, which already exists in all Westerners, articulate in a very few, inchoate in most. This Idea, in its wordless grandeur, its irresistible imperative, must be felt, and thus only men of the West can assimilate it. The alien will understand it as little as he has always understood Western creations and Western codes. In his victory parade in Moscow in 1945, the barbarian exhibited his Western captive slaves to the jeering crowds of his cities, and made them drag their national flags behind them in the dust. If any Westerner thinks that the barbarian makes nice distinctions between the former nations of the West, he is incapable of understanding the feelings of populations outside a High Culture toward that Culture. Tomorrow the captive slaves offered up to the annihilation-instincts of the Moscow mobs may be drawn from Paris, London, Madrid, as well as from Berlin. A continuation of the spiritual division of the West makes this not only possible but absolutely inevitable. Both the outer forces are working for the continued division of the West; within they are helped by the least worthy elements in Europe. This is addressed however to the only people that matter — the Westerners who can feel the Imperative of the Future working within them.

Our action-task is dictated for us by the fact that the soil of our Civilization is occupied by the outsider.

Yockey’s warning was prophetic. Today every major city of the West has a majority non-White population. Never mind jeers, the remaining Whites are robbed, raped and murdered.

The Idea, or at least a comparable ideal, has since been summed up in the catchword we know as The 14 Words:

We Must Secure The Existence Of Our PEOPLE And A Future For White Children

Unlike Yockey, David Lane and contemporary White nationalists have emphasized the importance of the PEOPLE over ideology.

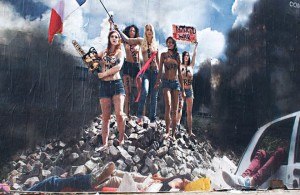

Image source: Culture Jamming Street Artist COMBO Stages Topless Spectacle in Paris.