The flip side of sweeping explanations that overlook the jews are the ones that are all about them. Where the jew-blind explanations are primarily for the non-jews, to keep us busy thinking about anything but jewish influence and power, the jew-centric explanations, which we’ll examine here, reflect how jews see the world and explain it to each other.

These jew-centric explanations of the world present a surreal, uncompromisingly one-sided view in favor of jews – how they’ve continually been wronged by others, most especially Europeans. This sick anti-White narrative is today the prevailing narrative in media, academia and politics. It comes from the jews.

New History: How Anti-Judaism Is at the Heart of Western Culture, by Adam Kirsh, Tablet Magazine, 13 Feb 2013:

The title of David Nirenberg’s new book, Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition, uses a term pointedly different from the one we are used to. The hatred and oppression of Jews has been known since the late 19th century as anti-Semitism—a label, it is worth remembering, originally worn with pride by German Jew-haters. What is the difference, then, between anti-Semitism and anti-Judaism? The answer, as it unfolds in Nirenberg’s scholarly tour de force, could be summarized this way: Anti-Semitism needs actual Jews to persecute; anti-Judaism can flourish perfectly well without them, since its target is not a group of people but an idea.

Nirenberg’s thesis is that this idea of Judaism, which bears only a passing resemblance to Judaism as practiced and lived by Jews, has been at the very center of Western civilization since the beginning. From Ptolemaic Egypt to early Christianity, from the Catholic Middle Ages to the Protestant Reformation, from the Enlightenment to fascism, whenever the West has wanted to define everything it is not—when it wants to put a name to its deepest fears and aversions—Judaism has been the name that came most easily to hand. “Anti-Judaism,” Nirenberg summarizes, “should not be understood as some archaic or irrational closet in the vast edifices of Western thought. It was rather one of the basic tools with which that edifice was constructed.”

This is a pretty depressing conclusion, especially for Jews destined to live inside that edifice; but the intellectual journey Nirenberg takes to get there is exhilarating. Each chapter of “Anti-Judaism” is devoted to an era in Western history and the particular kinds of anti-Judaism it fostered. Few if any of these moments are new discoveries; indeed, Nirenberg’s whole argument is that certain types of anti-Judaism are so central to Western culture that we take them for granted. What Nirenberg has done is to connect these varieties of anti-Judaism into a convincing narrative, working with original sources to draw out the full implications of seminal anti-Jewish writings.

The main reason why Judaism, and therefore anti-Judaism, have been so central to Western culture is, of course, Christianity. But Nirenberg’s first chapter shows that some persistent anti-Jewish tropes predate Jesus by hundreds of years. The Greek historian Hecataeus of Abdera, writing around 320 BCE, recorded an Egyptian tradition that inverts the familiar Exodus story. In this version, the Hebrews did not escape from Egypt but were expelled as an undesirable element, “strangers dwelling in their midst and practicing different rites.” These exiles settled in Judea under the leadership of Moses, who instituted for them “an unsocial and intolerant mode of life.” Already, Nirenberg observes, we can detect “what would become a fundamental concept of anti-Judaism—Jewish misanthropy.” This element was emphasized by a somewhat later writer, an Egyptian priest named Manetho, who described the Exodus as the revolt of an impious group of “lepers and other unclean people.”

As he will do throughout the book, Nirenberg describes these anti-Jewish texts not in a spirit of outrage or condemnation, but rather of inquiry. The question they raise is not whether the ancient Israelites were “really” lepers, but rather, why later Egyptian writers claimed they were. What sort of intellectual work did anti-Judaism perform in this particular culture? To answer the question, Nirenberg examines the deep history of Egypt, showing how ruptures caused by foreign invasion and religious innovation came to be associated with the Jews. Then he discusses the politics of Hellenistic Egypt, in which a large Jewish population was sandwiched uneasily between the Greek elite and the Egyptian masses. In a pattern that would be often repeated, this middle position left the Jews open to hostility from both sides, which would erupt into frequent riots and massacres. In the long term, Nirenberg writes, “the characteristics of misanthropy, impiety, lawlessness, and universal enmity that ancient Egypt assigned to Moses and his people would remain available to later millennia: a tradition made venerable by antiquity, to be forgotten, rediscovered, and put to new uses by later generations of apologists and historians.”

This “exhilirating intellectual journey”, presented as a “new history”, is really just the same old tired promotion of the same old jew-excusing apologia, replete with persistent jewish tropes:

-

That the defining feature of non-jews, and specifically “the West”, i.e. Whites, is “anti-jewism”.

-

That jews are powerless, innocent victims.

-

That non-jews try to invert and otherwise manipulate history.

These are actually just variations on the most common jewish trope of all: The problem is not the jews, it’s anyone and everyone else!

Jews are not unaware that there are other points of view. They simply do not compare to their own. Rather than denying the idea that, “the Hebrews did not escape from Egypt but were expelled as an undesirable element”, they invert and thereby co-opt it. Taken together with the hundreds of conflicts and expulsions since, the moral of the jewish narrative is that everyone else is the undesirable element, the “lepers”.

With the rise of Catholic polities in the Middle Ages, anti-Judaism took on a less theological, more material cast. In countries like England, France, and Germany, the Jews held a unique legal status as the king’s “servants” or “slaves,” which put them outside the usual chain of feudal relationships. This allowed Jews to play a much-needed but widely loathed role in finance and taxation, while also demonstrating the unique power of the monarch. The claim of the Capet dynasty to be kings of France, Nirenberg shows, rested in part on their claim to control the status of the Jews, a royal prerogative and a lucrative one: King after king plundered “his” Jews when in need of cash. At the same time, being the public face of royal power left the Jews exposed to the hatred of the people at large. Riots against Jews and ritual murder accusations became popular ways of demonstrating dissatisfaction with the government. When medieval subjects wanted to protest against their rulers, they would often accuse the king of being in league with the Jews, or even a Jew himself.

The common thread in Anti-Judaism is that such accusations of Jewishness have little to do with actual Jews. They are a product of a Gentile discourse, in which Christians argue with other Christians by accusing them of Judaism. The same principle holds true in Nirenberg’s fascinating later chapters. When Martin Luther rebelled against Catholicism, he attacked the church’s “legalistic understanding of God’s justice” as Jewish: “In this sense the Roman church had become more ‘Jewish’ than the Jews.” When the Puritan revolutionaries in the English Civil War thought about the ideal constitution for the state, they looked to the ancient Israelite commonwealth as described in Judges and Kings.

Surprisingly, Nirenberg shows, the decline of religion in Europe and the rise of the Enlightenment did little to change the rhetoric of anti-Judaism. Voltaire, Kant, and Hegel all used Judaism as a figure for what they wanted to overcome—superstition, legalistic morality, the dead past. Finally, in a brief concluding chapter on the 19th century and after, Nirenberg shows how Marx recapitulated ancient anti-Jewish tropes when he conceived of communist revolution as “the emancipation of mankind from Judaism”—that is, from money and commerce and social alienation.

Religion, no religion, kings, no kings – the common thread is jews somehow managing to get special status and privileges. The jewish narrative explains this by imagining ubiquitous “anti-jews” who only imagine jews exist. Unsurprisingly, the “exhilirating intellectual journey” concludes by imagining Marx not as part and parcel of a quintessentially jewish revolutionary tradition but as an “anti-jew”.

Not until the very end of Anti-Judaism does he touch, obliquely, on the question of what this ancient intellectual tradition means for Jews today. But as he suggests, the genealogy that connects contemporary anti-Zionism with traditional anti-Judaism is clear: “We live in an age in which millions of people are exposed daily to some variant of the argument that the challenges of the world they live in are best explained in terms of ‘Israel.’ ” For all the progress the world has made since the Holocaust in thinking rationally about Jews and Judaism, the story Nirenberg has to tell is not over. Anyone who wants to understand the challenges of thinking and living as a Jew in a non-Jewish culture should read Anti-Judaism.

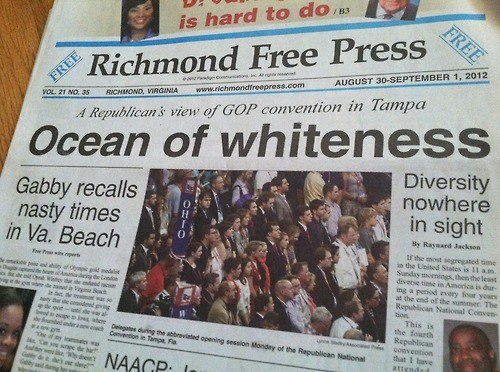

More important, let’s touch on what this all means for Whites today. We live in an age in which millions of Whites are exposed to, and to a terrifying extent, have accepted the jewish narrative – a viewpoint utterly hostile to themselves.

Whoever did whatever to whom in the past, today it is jews who police the mainstream media and public political discourse and fill it with terms like “anti-semitism”, “Israel” and “Holocaust”. These terms reflect their obsession with themselves and their best interests, which includes imposing their way of seeing the world, their self-obsessions, onto everyone else.

Reinforcing this point, a “related content” link on the article above takes the reader to an older article from October 2011, Ron Rosenbaum Confronts ‘The End of the Holocaust’:

Alvin Rosenfeld is a brave man, and his new work is courageous. The book is called The End of the Holocaust, and it is not reluctant to take on the unexamined pieties that have grown up around the slaughter, and the sentimentalization that threatens to smother it in meretricious uplift.

The real “end of the Holocaust,” he argues, is the transformation of it into a lesson about the “triumph of the human spirit” or some such affirmation. Rosenfeld, the founder and former director of the Jewish studies program at Indiana University, which has made itself a major center of Jewish publishing and learning, is a mainstream scholar who has seen the flaw in mainstream Holocaust discourse. He has made it his mission to rescue the Holocaust from the Faustian bargain Jews have made with history and memory, the Faustian bargain that results when we trade the specifics of memory, the Jewishness of the Holocaust, and the Jew-hatred that gave it its rationale and identity, for the weepy universalism of such phrases as “the long record of man’s inhumanity to man.”

The impulse to find the silver lining is relentless, though. Suffering and grief must be transformed into affirmation, and the bleak irrecoverable fate of the victims must be given a redemptive aspect for those of us alive. In fact it’s an insult to the dead to rob their graves to make ourselves feel better. One recent manifestation Rosenfeld has shrewdly noticed is the way there has been a subtle shift in the popular representation of the Holocaust—a shift in the attention once given to the murdered victims to comparatively uplifting stories of survivors, of the “righteous gentiles,” of the scarce “rescuers,” and the even scarcer “avengers,” e.g., Quentin Tarantino’s fake-glorious fictional crew.

Rosenfeld is not afraid to contend with the fact that, as he writes, “with new atrocities filling the news each day and only so much sympathy to go around, there are people who simply do not want to hear any more about the Jews and their sorrows. There are other dead to be buried, they say.” The sad, deplorable, but, he says, “unavoidable” consequence of what may be the necessary limits of human sympathy is that “the more successfully [the Holocaust] enters the cultural mainstream, the more commonplace it becomes. A less taxing version of a tragic history begins to emerge, still full of suffering, to be sure, but a suffering relieved of many of its weightiest moral and intellectual demands and, consequently easier to be … normalized.”

Normalized? The Holocaust as one more instance in the long chronicle of “man’s inhumanity to man”? Rosenfeld’s book offers a welcome contrarian take on the trend. Yes, we’ve had enough, as Rosenfeld points out, of museums that cumulatively obscure memory in a fog of well-meaning but misleading inspirational brotherhood-of-man rhetoric.

Here, stripped of the usual misleading brotherhood-of-man rhetoric, is an even more specific and virulent example of jewish self-obsession. Rosenbaum and Rosenfeld see sympathy, everyone’s sympathy, as something the jews alone deserve.

What we haven’t had enough of is a careful consideration of the implications of the Holocaust for the nature of human nature. As George Steiner told me (for my book, Explaining Hitler), “the Holocaust removed the re-insurance from human hope”—the psychic safety net we imagine marked the absolute depth of human nature. The Holocaust tore through that net heading for hell. Human nature could be—at the promptings of a charismatic and evil demagogue, religious hate, and so-called “scientific racism”—even worse than we imagined. No one wants to hear that. We want to hear uplifting stories about that nice Mr. Schindler. We want affirmations!

And the fact that it was not just one man but an entire continent that enthusiastically pitched in or stood by while 6 million were murdered: Doesn’t that call for us to spend a little time re-thinking what we still reverently speak of as “European civilization”? Or to investigate the roots of that European hatred? How much weight do the Holocaust museums give to the two millennia of Christian Jew-hatred, murderous pogroms, blood libels, and other degradations? Or do they prefer to focus on “righteous gentiles” in order to avoid offending their gentile hosts?

And for all their “reaching out” and “teachable moments,” how much do the Holocaust museums and Holocaust curricula connect the hatred of the recent past with contemporary exterminationist Jew-hatred, the vast numbers of people who deny the first, but hunger for a second, Holocaust? It’s a threat some fear even to contemplate—the potential destruction of the 5 million Jews of Israel with a single well-placed nuclear blast—a nightmarish but not unforseeable possibility to which Rosenfeld is unafraid to devote the final section of his book.

Rosenbaum, a perpetually offended professional jew, thinks the problem with jews is that they aren’t self-obsessed and offensive enough. The threat, as he sees it, is “human nature”, which is just another way of saying everyone and anyone else.

Rosenbaum goes on and on in this vein, expressing his contempt for “the non-jewish majority” because, in his opinion, they don’t care enough about the jews.

Consider the Faustian bargain that Holocaust museums in America have so often made with the non-Jewish majority: The survivors and eyewitnesses of the Holocaust are dying, and the only way to get Americans to care about the destruction of the Jews, the only way we will get a (nearly) front row seat on the National Mall in Washington for our Holocaust museum, is by convincing Americans that the Holocaust can be a “teachable moment” in America’s uplifting struggle against intolerance. Rosenfeld calls this bargain “the Americanization of the Holocaust,” and even though he’s on the executive committee of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum he’s not happy about the tendency.

In discussing, for instance, the Los Angeles-based Museum of Tolerance (the Simon Wiesenthal Center’s Holocaust museum), he says that “by situating the Holocaust within a historical framework that includes such quintessentially American experiences as the Los Angeles riots and the struggle for black civil rights, both of which are prominently illustrated, the Museum of Tolerance relativizes the catastrophe brought on by Naziism in a radical way. America’s social problems, for all their gravity, are not genocidal in character and simply do not resemble the persecution and systematic slaughter of European Jews during World War II.” It’s a critique I first saw articulated by Jonathan Rosen in a 1993 New York Times op-ed called “The Misguided Holocaust Museum” back when the museum on the Mall was first opening. At first I was surprised, but then I was persuaded, at least to a certain extent, by Rosen’s impassioned dissent from the conventional wisdom.

And of course there is the difficult question of how one compares such tragedies. Why not a Cambodian genocide museum? In what ways are the Cambodian, the Armenian, and the Rwandan genocides similar and different from the Nazi genocide? If the Rodney King riots do not deserve being placed on the same plane shouldn’t the casualties of slavery in America, an institution that killed the bodies and murdered the souls of those who survived, count just as much?

There’s an argument that it’s a politically savvy heuristic strategy to unite with other sufferers against the murderous haters rather than set our suffering apart. And Jews have a strong record of concern for the sufferings of others. Solidarity! But Rosenfeld is on a mission not to allow the differences of the identity of the Jewish victims to disappear, and he is both a moral thinker and an astute cultural critic.

Rosenbaum’s argument: Hey jews, you’re letting everyone forget that it’s all about the jews.