From the Bastille to the boulevard: The long history of Jewish revolt, by Shuki Sadeh, Ido Efrati, Haaretz Daily Newspaper, 2 Sept 2011:

From the Bastille to the boulevard: The long history of Jewish revolt, by Shuki Sadeh, Ido Efrati, Haaretz Daily Newspaper, 2 Sept 2011:

One hot day in the summer of 1967, a young, frizzy-haired guy named Abbie Hoffman tried to go into the visitors’ entrance of the building in which the New York Stock Exchange is located. When the guard stopped him, Hoffman said: “We are Jews and you are an anti-Semite who is not letting us in.” The disconcerted guard let Hoffman and his hippie-friends go up to the visitors’ gallery.

Jews have traditionally taken a particular interest in the successes of their people in every generation and in every field of endeavor. This Jewish “bookkeeping” is mostly tendentious and usually ignores the circumstantial and environmental conditions that made these success stories possible. Indeed, for the most part, it prefers to attribute these achievements to the genetic makeup of the Chosen People.

“The list of Jews who have been involved in leading revolutions [since the middle of the 19th century] is very long,” explains Prof. Moshe Zimmermann of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem’s history department. “When a social group is not satisfied with its situation and feels it cannot change it – it will support a revolution. The Jews were not satisfied because they did not have privileges granted to other sectors and therefore the idea of revolution – whether communist or liberal – was attractive to them.

According to Prof. Moshe Zuckermann, a historian at Tel Aviv University, revolution was not the only option for Jews. They had least two other options.

“One was assimilation,” he explains, “as happened in Germany in the 19th century, and the other was going in the Zionist direction, a possibility that arose at the end of that century. If a Jew did not choose one of those two directions, his remaining alternative was to change the society at large – and therefore became a revolutionary.”

Trotsky was surrounded by quite a number of Jews, among whom his brother-in-law, Lev Kamenev, and Grigory Zinoviev stood out. “It is said jokingly,” comments Miron, “that when Lenin would leave the room, Trotsky was able to organize a minyan [prayer quorum].”

In Hungary, in another example, Bela Kun, a young man in his 30s, was among the founders of the Soviet Republic in Hungary in 1919. When it collapsed after 133 days, Kun went into exile in Russia, and was killed in one of Stalin’s purges at the end of the ’30s.

“Kun operated within a reality in ferment: Nearly half of the Hungarian journalists were Jewish, as well as the lawyers and doctors – even though they constituted only 5 percent of the population,” Silber explains. “At the end of World War I, Kun seized power in Hungary. He headed a government of 35 commissars, nearly all of them Jewish, and the impression was that a Jewish government really had been created. This led to a wave of anti-Semitism and terror against Jews.”

“In Germany there were various revolutionary ‘focal points’ dominated by Jews,” says Miron. “Kurt Eisner led the ‘Bavarian Soviet Republic,’ which briefly ruled in Bavaria. In Munich, there were three attempts at a revolution, all of them were led by Jews and all of them failed.”

Rosa Luxemburg, a Polish-born Jewess, was one of the founders of the Communist Party in Germany.

“Jewish revolutionaries for the most part live on the margins of Jewish society and sometimes cut off ties with the community,” notes Prof. Avi Saguy, head of the program for hermeneutics and a lecturer in philosophy at Bar-Ilan University. According to him, tikkun olam (repairing the world ) is a profound Jewish ethos – but a conservative rather than a revolutionary one.

“To say that in the Jewish genes there is a revolutionary element is utter nonsense,” says Prof. Zimmermann. “The Jews, by virtue of being a minority and because they were a religious group, adopted various types of behavior – which also explains the support for revolutions. The origin of the demand for social justice is indeed rooted in Jewish tradition, but in modern conditions, it can be said that it lies in revolutionary tendencies.”

Zuckermann, too, says there is no connection between the revolutionaries’ Jewishness and their political choices: “The discourse did not revolve around ultra-Orthodox religious Judaism, but rather around the Judaism that emerged in the period of the Enlightenment. From the moment the Jews integrated into the civil society of the 19th century – which, although it declared that they were emancipated, in fact did not accept them – they had a collective interest in changing society. Bourgeois civil society perceived the Jews in a new light: not only in a religious context, but also in socioeconomic one.”

Emanicipation of society

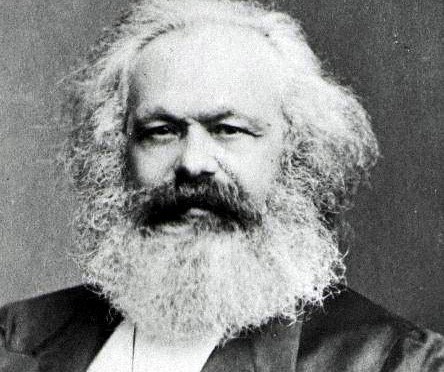

The most significant expression of the separation between the Jew’s social status and his tradition is found in the writings of Karl Marx, whose philosophy had a crucial influence on the revolutionaries of the 19th and 20th centuries. Born in Germany in 1818, Marx came from a family of rabbis but his father converted and became a Lutheran.

In his 1844 essay “On the Jewish Question,” one of his early writings, Marx related to the secular status of the Jews in society and characterized them as a people identified with commerce and the accumulation of wealth.

“Let us not look for the secret of the Jew in his religion,” he wrote, “but let us look for the secret of his religion in the real Jew. What is the secular basis of Judaism? Practical need, self-interest. What is the worldly religion of the Jew? Huckstering. What is his worldly God? Money. Very well then! Emancipation from huckstering and money, consequently from practical, real Judaism, would be the self-emancipation of our time. An organization of society which would abolish the preconditions for huckstering, and therefore the possibility of huckstering, would make the Jew impossible. His religious consciousness would be dissipated like a thin haze in the real, vital air of society …

“We recognize in Judaism, therefore, a general anti-social element of the present time, an element which through historical development – to which in this harmful respect the Jews have zealously contributed – has been brought to its present high level, at which it must necessarily begin to disintegrate. In the final analysis, the emancipation of the Jews is the emancipation of mankind from Judaism.” There are those who saw in Marx’s sharp words an expression of anti-Semitism and a denial of his Jewish past. However, in general he is perceived as a serious social theoretician, who called for the elimination of religious separatism of any kind and for abolishing economic commerce, on the way to creating an egalitarian, classless civil society.

“Most of the great revolutionaries,” says Zuckermann, “did not relate to their Judaism. People like Karl Marx, Leon Trotsky and Rosa Luxemburg did not talk about emancipating the Jews from their Judaism, but rather about human emancipation, whereby people need to liberate themselves from social structures that create the oppression of various groups in the society, among them the Jews.”

Jews, jews, jews. Jews are so obsessed with themselves that they write stories bragging even about the mass murder and mayhem their tribemates have caused, turning European society upside down, spinning it as good and righteous. Then, perhaps realizing that this story may not fly, they hedge somewhat by lamely claiming it wasn’t really jews as jews.

But of course the story is about jews as jews. That’s what 9/10ths of it is about and that’s why it was published by Haaretz.