Podcast: Play in new window | Download

We make here a brief digression to provide some context for Francis Parker Yockey’s quotes from Napoleon.

First, we’ll consider an explication provided by Eric Voegelin. Who is Voegelin? Eric Voegelin and Ancient Israel:

Eric Voegelin (1901-1985) has been described as a political philosopher and a philosopher of history. His magnum opus Order and History is regarded by partisans in terms of scientific scholarship combined with theological insight.

He watched the Austrian and German republics fall in the 1930s when the Nazis gained power. Voegelin loathed the irrationality and racism of Nazism, and eventually lost his admiration for Nietzsche, of whom he was very critical in some of his later writings. However, it was not merely the “will to power” that aroused his disdain. Although a Lutheran in his upbringing, Voegelin came to distrust the ecclesiastical establishment. During the 1930s, all except one of the Christian clergy he knew were Nazis. (3)

He exposed himself to danger in being unwilling to align himself with Hitler’s cause. In 1938, he was dismissed from his professorial post at the university of Vienna, and narrowly escaped from the Gestapo. Fleeing from the Nazi environment, Voegelin moved with his wife to America, where he lived for the rest of his life, becoming an American citizen.

Any opinion-shaper Lawrence Auster approved of must be regarded with suspicion:

Auster revered Eric Voegelin, another epic-level falsifier of reality. Voegelin was the source of most of Auster’s stupid ideas about “gnosticism”. Voegelin claimed that gnosticism was responsible for Marxism.

Voegelin’s discussion of Napoleon is part of a broader examination of Auguste Comte:

Isidore Auguste Marie François Xavier Comte (19 January 1798 – 5 September 1857), better known as Auguste Comte (French: [oɡyst kɔ̃t]), was a French philosopher. He was a founder of the discipline of sociology and of the doctrine of positivism. He is sometimes regarded as the first philosopher of science in the modern sense of the term.

Comte’s social theories culminated in the “Religion of Humanity“, which influenced the development of religious humanist and secular humanist organizations in the 19th century. Comte likewise coined the word altruisme (altruism).

Thomas Huxley described Comte’s religion as “Catholicism minus Christianity”.

The following excerpt is taken from Voegelin’s History of Political Ideas: Crisis and the Apocalypse of Man, the section titled The Apocalypse of Man: Comte, p. 204:

Napoleon – Russia and the Occidental Republic

More specifically, the political program of [Auguste] Comte is related to the ideas of Napoleon. This is a question of which Comte is strictly reticent; Napoleon appears in his work only in order to be condemned as the “génie rétrograde” [retrograde engineering]. Nevertheless, the relation exists. In particular Comte’s conception of the Occident is hardly conceivable before the consolidation of the Occidental idea through Napoleon’s struggle with the new Orient, that is, with Russia. Let us pass in review a few utterances of Napoleon: “There are only two nations in the world. The one lives in the Orient, the other occupies the Occident. The English, French, Germans, Italians, and so on, are governed by the same civil law, the same mores, the same habits, and almost the same religion. They are all members of one family, and the men who want to start war among them, want a civil war.” 43 The means for abolishing this state of Occidental civil war would be the political unification of the West. “There will be no peace in Europe except under a sole chief, under an emperor who has kings as his officers and distributes kingdoms to his lieutenants.” 44 The political should be followed by the institutional and civilizational unification. “All the united countries must be like France; and if you unite them to the Pillars of Hercules [at the Straight of Gibraltar, southern tip of Spain] and to Kamchatka [far-eastern Russia, a pennisula jutting into the Pacific ocean], the laws of France must extend everywhere.” 45 And in retrospect: “Why did my Code Napoléon not serve as the basis for a Code européen, and why my Université impériale not as the model for a Université européenne? In this manner we would have formed in Europe one and the same family. Everybody, when traveling, would have found himself at home.” 46 This Occident is a unit not only because of its internal history and coherence; it is forced toward a still more intense unification because of its defensive position against Russia.

Napoleon elaborates this problem on the occasion of the Russian plans with regard to Turkey. The ideas of the tsar revolved around the conquest of Turkey. “We discussed several times the possibility and eventuality of its partition, and the effect on Europe. At first sight the proposition attracted me. I considered that the partition would extend the progress of civilization. However, when I considered the consequences more coolly, when I saw the immense power that Russia would gain, and the great number of Greeks in the provinces now subject to the sultan who then would join a power which is already colossal, I refused roundly to have a part in it.” The principal difficulty was Russia’s design on Constantinople, for “Constantinople, c’est l’Empire du monde.” [is the Empire of the world] It was obvious that France, “even if she possessed Egypt, Syria, and India, would be nothing in comparison with what these new possessions would make of Russia. The barbarians of the north were already much too powerful; after this partition they could overrun all Europe. I believe this still.” 47 In another mood he sees this danger present even now. “If Russia finds an emperor who is courageous, impetuous, capable, in brief: a tsar who has a beard on his chin, then Europe is his. He can begin his operations on the German soil itself, at a hundred leagues from Berlin and Vienna, whose sovereigns are the only obstacles. He enforces the alliance of the one, and with his help he will defeat the other. From this moment he is in the heart of Germany.” At this junction, Napoleon puts himself in the place of the conqueror, and continues: “Certainly, if I were in this situation, I would arrive at Calais according to a timetable in moderate marches; and there I would find myself master and arbiter of Europe.” Then, in the conversation, the dream of the conquest of the Occident separates from the Russian problem. He is now himself the conqueror who is master and arbiter of Europe. And he addresses his interlocutor: “Perhaps, my friend, you are tempted to ask me, like the minister of Pyrrhus asked his master: And what is all this good for? I answer you: For founding a new society and for the prevention of great disasters. Europe waits for this relieving deed and solicits it: the old system is finished, and the new one is not yet established, and it will not be established without long and violent convulsions.” 48 Let us, finally, recall that Napoleon also dreamed of making Paris the seat of the spritual power of the Occident as of its temporal power. With the pope in Paris, the city would have become “the capital of the Christian world, and I would have directed both the religious world and the political. . . . I would have had my religious sessions like my legislative sessions; my councils would have been the representation of Christianity; the popes would have been only its presidents; I would have opened and closed these assemblies, approved and published their decisions, as it had been done by Constantine and Charlemagne.” 49

43. This and the following quotations are taken from the collection Napoléon, Vues politiques, introduction by Adrien Dansette (Rio de Janeiro: Amérie-Edit, n.d.). The original edition is Paris, 1839. The passage quoted is from September 1802, p. 340.

44. “A Miot de Mélito,” 1803, in ibid.

45. “Au conseil d’état,” July 1805, in ibid., 341.

46. “A las cases, Sainte-Hélène,” in ibid.

47. “A O’Meara, Sainte-Hélène,” in ibid., 339 f.

48. “A las cases, Sainte-Hélène,” in ibid., 337 f.

49. “A las cases, Sainte-Hélène,” in ibid., 181 f.

Roman Bernard’s Nation-States, the European Union and the Occident (1/3) asks, “how we get from stato-national feeling to Pan-Occidental awareness”:

Western European nations originate from the Carolingian Empire, which was shared out in 843 A.D. between the three grandsons of Charlemagne.

From the dislocation of the Western Empire, as it was then named, emerged thus three states. These were Francia Occidentalis (which would become France) and Francia Orientalis (later the Holy Roman Empire, which was Germanic). Lothair kept an awkwardly-shaped strip in the middle, including all the regions European powers would seek to conquer up to WW2: what would later become the Low Countries, Rhineland, Alsace, Switzerland, Northern Italy.

Francia Orientalis, AKA East Francia, comprised most of contemporary Germany, Austria and Croatia.

A comment on the previous installment from Marcus linked Napoleon I: Visionary Racial Nationalist:

In the bolded quote, Napoleon makes the right case for ethnonationalism, in contrast to many White Nationalists of today who look to moral or scientific justifications for their ideology.

“Years later, questioned by his friend Truguet about what he had done in Saint-Domingue, an enraged Bonaparte declared that, had he been in Martinique during the Revolution, he would have supported the English rather than accept an end to slavery. “I am for the whites because I am white; I have no other reason, and that one is good,” he said. “How is it possible that liberty was given to Africans, to men who had no civilization, who did not even know what the colony was, what France was? It is perfectly clear that those who wanted the freedom of the blacks wanted the slavery of the whites.”

This is a moral justification based on a particularist, group-centric understanding of right and wrong.

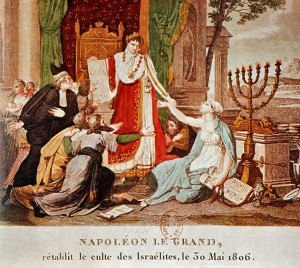

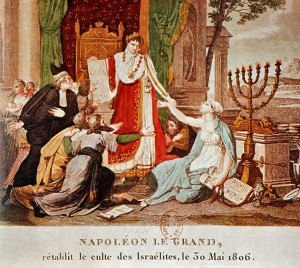

Napoleon and the Jews, at Wikipedia, describes the jews’ positive regard for Napoleon and his candid expressions of his negative regard for them:

Napoleon Bonaparte of the First French Empire enacted laws that emancipated European jews from old laws restricting them to ghettos, as well as the many laws that limited Jews’ rights to property, worship, and careers.

The net effect of his policies, as a result, significantly changed the position of the Jews in Europe, and he was widely admired by the Jews as a result. Starting in 1806, Napoleon passed a number of measures supporting the position of the Jews in the French Empire

This attitude can be seen from the letter he wrote on the 29th of November 1806, to Champagny, Minister of the Interior:

[It is necessary to] reduce, if not destroy, the tendency of Jewish people to practice a very great number of activities that are harmful to civilisation and to public order in society in all the countries of the world. It is necessary to stop the harm by preventing it; to prevent it, it is necessary to change the Jews. […] Once part of their youth will take its place in our armies, they will cease to have Jewish interests and sentiments; their interests and sentiments will be French.

Privately, in a letter to his brother Jerome Napoleon dated 6 March 1808 he makes his views explicit:

I have undertaken to reform the Jews, but I have not endeavoured to draw more of them into my realm. Far from that, I have avoided doing anything which could show any esteem for the most despicable of mankind.

Napoleon’s indirect influence on the fate of the Jews was even more powerful than any of the decrees recorded in his name. By breaking up the feudal trammels of mid-Europe and introducing the equality of the French Revolution he effected more for Jewish emancipation than had been accomplished during the three preceding centuries.

Whatever the reason, from his presumption that they could be assimilated or changed it is apparent that Napoleon misunderstood and underestimated the jews. The results have been disastrous for European man.